Introduction

In the summer of 2022, I visited the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Duke University to research the papers of the late Professor Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972). As I described elsewhere, Prof. Heschel spearheaded a project to collect Hasidic archival materials during the immediate post-Holocaust years. In addition to leading a team of researchers tasked with collecting original manuscripts and transcribing oral histories, Heschel was engaged in a years-long research project on the early history of Hasidism. In 1954, Heschel was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to write a book on the Ba’al Shem Tov.

Unfortunately, this book never came to fruition. However, Heschel published several articles on Hasidism's early history, focusing on the colleagues and disciples of the Besht. These articles were compiled and translated into English by Heschel’s student Rabbi Samuel Dresner (1923–2000) and published in book form as The Circle of the Baal Shem Tov: Studies in Hasidism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985).

These published articles, however, constitute only a fraction of the work undertaken by Heschel. Heschel’s papers contain thousands of pages of original and photocopied materials, copious citations, research notes, and early article drafts on the history of the Besht, his historical milieu, and his close associates and opponents. A mammoth effort is required to organize and decipher Heschel’s manuscripts and produce a coherent scholarly study of these documents. In this brief article, I will highlight one such document relating to Heschel’s research on early Hasidism.

One day, as I was researching Heschel’s archive, I came across a box containing various documents and Heschel’s research notes on the circle of the Besht. As I was perusing through the contents of the box, I noticed two typed pages containing the heading מעשה מבעש"ט זצוקללה"ה (a story of the Besht, of saintly memory). As I took a closer look at the first page, I saw that the story was written in Yiddish and contained some handwritten corrections and notes. My initial hunch of the identity of the person who wrote the notes was confirmed when I examined the second page; it was the handwriting of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson OBM (1902-1994). (This would have gone virtually unnoticed by many researchers, but as someone who grew up in the Chabad community of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, NY, the Rebbe’s handwriting was immediately recognizable to me).

How did this document end up in Heschel’s archive? Evidently, the late Lubavitcher Rebbe sent this to Heschel. My working assumption is that Heschel requested materials on Hasidism from the late Lubavitcher Rebbe and/or his father-in-law Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn (1880-1950) that were in the possession of Chabad. It is possible that Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson was acquainted with Heschel during the time they both studied together at the Humbolt University of Berlin during the late 1920s and early 1930s. At any rate, both Lubavitcher Rebbes sent letters to Heschel, which are held in Heschel’s archive.

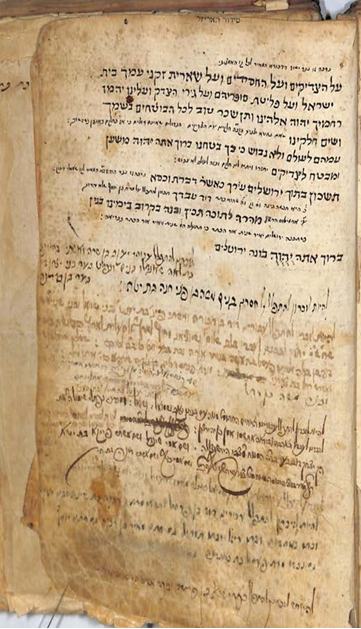

In addition, Heschel obtained special permission to examine the Sidur of the Ba’al Shem Tov which is held in the Chabad library. Heschel’s notes containing transcriptions of various lists of names written by followers of the Besht in the margins of the Besht’s Siddur asking him to mention them in his prayers that he jotted down when he visited the Chabad library are included in the Heschel papers.

The unpublished story of the Besht highlighted in this article was apparently copied from another manuscript for Heschel’s benefit. After the typist copied the manuscript, the Lubavitcher Rebbe reviewed it, corrected it, and added several notes. The original source of the story still remains unknown.

A story of the Besht, of righteous memory

Once 72 rabbis gathered to excommunicate the Besht, of saintly memory. [The reason for this was] because before the Besht was revealed to the entire world and performed great miracles, the 72 rabbis said that they [the stories they relate about him] were not true, God forbid. Consequently, 71 rabbis traveled to Cracow to get the Rabbi of Cracow to join them so that there would be a total of 72 [rabbis]. They [the 71 rabbis] related to him [the Rabbi of Cracow] the miracles of the Besht, may his memory protect us, and they told him that they are considering placing him in excommunication, God forbid. The Rabbi of Cracow replied that this could not be done without him [the Besht] being present. He therefore advised [them the following:] that living not far from him is a good friend with whom he had studied together. So he will write to him to inquire regarding the Besht’s deeds and manner of conduct. The 71 rabbis replied that this matter could not be determined through a letter; instead, [they advised him that] he should travel to him [his friend]. He [his friend] was called R. Gershon Kitever, the brother-in-law of the Besht, of blessed memory. Thus, the matter was settled, that he [the Rabbi of Cracow] should go on the journey. On his journey, he arrived in a shtetl a day earlier than R. Gershon OBM. He visited an inn and spent the night there. In the meantime, it so happened that R. Gershon spent that very Shabbat at the Besht, OBM. The Besht, may his memory protect us, told him to return home because a distinguished guest, whom he had not seen for a long time, approximately 30 years, was traveling to visit him. And he [the Besht] instructed him [R. Gershon] to travel toward him [the Rabbi of Cracow], in the very same shtetl where the Rabbi of Cracow was spending the night. In short, he came to the very shtetl and the very inn where the Rabbi of Cracow was lodging. Reb Gershon found him [the Rabbi of Cracow] fast asleep, and R. Gershon OBM also laid down to rest. The Rabbi of Cracow was the first to rise, and he recited the blessing on the Torah. As soon as R. Gershon OBM heard a familiar voice, he arose, and he recognized him (the Rabbi of Cracow), and they both rejoiced tremendously. R. Gershon OBM inquired about his whereabouts and travels. So, the Rabbi of Cracow told him that he was, in fact, traveling to see him. He related to R. Gershon OBM the entire story about the 71 rabbis and what they were planning to do, and he was coming to R. Gershon OBM to find out what the Besht OBM was up to. R. Gershon OBM replied to the Rabbi of Cracow, “How can I tell you about his many miracles? They are too numerous and wondrous to describe. I will just tell you one story that just happened on Shabbat, on the night of the holy Shabbat: The holy Besht would always recite ‘Torah’ (teachings), and all of his teachings had to be consistent with the writings of the Holy Ari [Rabbi Issac Luria]. If the teachings did not concur with the writings of the Holy Ari, his students would ask him, ‘Rebbe, the writings of the Ari do not match your teachings.’ Probably, the disciples had his [the Besht’s] permission to bring to his attention that his words were not consistent with the writings of the Holy Ari. When it happened that the Besht, may his memory protect us, taught a teaching and the disciples told him, ‘Rebbe, it is not written thus in the writings of the Holy Ari,’ he would lower his head and contemplated [the matter] until his teachings conformed to the writings of the Ari. This Shabbat night, the Besht expounded upon the kavanot [mystical intentions] of the mikva [ritual bath]. And the disciples raised objections based on the writings of the Holy Ari about the intentions of the mikva. So the Besht, may his merit protect us, lowered and bowed his head. Several hours passed, during which all the students fell asleep; I, however, fought very hard not to dose off; I bit my hand to prevent myself from falling asleep. However, nothing helped. Several hours went by until I also fell asleep. In my sleep, I envisioned myself in Gan Eden [the Garden of Eden]. I saw Gan Eden as it ought to look; people donning shtreimels [fur hats word by Hasidim] were moving about, and the illumination was endless. Suddenly, a shout rang out, and they cleared a path for the Besht to walk through. When he arrived, they brought him an elegant chair upon which to sit. Afterward, another shout rang out that they should clear a path for the Holy Ari to walk through. In short, the Ari, of saintly memory, also arrived, and they brought a chair for him, and he sat down next to the Besht, may his merit protect us. The Besht, may his merit protect us, asked the Holy Ari, ‘What is the final word regarding the intentions of the Mikva.’ The Holy Ari answered, ‘As you say,’ The Besht asked him further, ‘but in your writings it does not say so?’ The Holy Ari told him, ‘In my times, those were the intentions, but today they are as you say.’ The Besht, may his merit protect us, asked him, ‘Who will testify that the final word is as I say.’ The Holy Ari replied, ‘Your Gershon is currently present; he will testify that this is what I said.’ So the Besht grabbed me by my hand and shouted, ‘Gershon, you hear what the Holy Ari said, that the intentions of the Mikva are as I say?’” To make a long story short, the Rabbi of Cracow went home and related to the 71 rabbis the story that R. Gershon OBM told him, and he told them that he [the Besht] is the greatest in the world. I heard this from my honorable father-in-law on the Shabbat of Parshat Naso, in the year 5653 here in Warsaw.

Some preliminary observations about the story

Given the many fanciful legends surrounding the Besht’s life, it is extremely challenging to tease out fact from fiction. Hence, I will not even attempt to investigate whether this story may be based on historical events. Instead, my focus will be on the hagiographical functions of the story in portraying a particular image of the Besht.

By “hagiographical functions,” I mean the way a hagiographical tale deliberately attempts to portray its protagonist in a certain light. This portrayal may be based on fact, fiction, or both. It also may consist of a polemical account intended to counter alternative perceptions or accusations that cast the protagonist in a less favorable light. A key feature of the hagiographical function is its self-conscious nature. It does not innocently recount neutral biographical details; rather, it is (overtly or covertly) agenda-driven and seeks to portray its protagonist in a particular light.

Concerning our story, some of its “hagiographical functions” are fairly transparent. First, it deals with the theme of opposition to Hasidism. There is a long history of opposition to Hasidism, and this story relates to this phenomenon by recounting an attempt to place the Besht in ḥerem (a Halakhic form of excommunication). In this story, the Besht is one step ahead of the rabbis who want to excommunicate him and outwit them. As in many other tales of the Besht, the plotline of this story conforms to the trope of the “converted opponent,” i.e. the initial opponents of the Besht who later became his most devoted followers. Second, it highlights the Besht’s miraculous powers and his great feats as a בעל רוח הקודש (someone upon whom the “holy spirit” rests and is therefore endowed with clairvoyant powers). Third, this story proclaims the superiority of the Besht over the Arizal. It does so by relating that the Besht’s authority and superiority were confirmed in the heavenly realm (and thus upheld in the World of Truth). Consequently, it affirms the status of the Besht as a mystic who is not only as great as the Arizal but even supersedes him.

Another unique feature of this story is the detail about the group 72 rabbis who assembled to excommunicate the Besht. This is a significant detail that does not appear in other versions. The significance of this exact number is unclear. Possibly, it symbolizes a great court like a great rabbinic tribunal like the Sanhedrin, but a Sanhedrin consisted of 71 judges, not 72. However, several rabbinic sources mention the existence of 72 elders (see Mishna Yadayim 4:2; Masechet Soferim 1:7 and 2:11. See also the commentary Tiferet Yisrael on Sanhedrin, chapter 1, no. 41). The tradition that the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Torah) was written by 72 elders should also be noted. The number of 72 sages mentioned in our story may be based on this tradition of 72 elders.

In a forthcoming study, I will present and analyze multiple variants of this story and also highlight the dynamic and fluid nature of the Hasidic tale.